How the Poor Design of Social Housing Led to the Gentrification on North Kensington

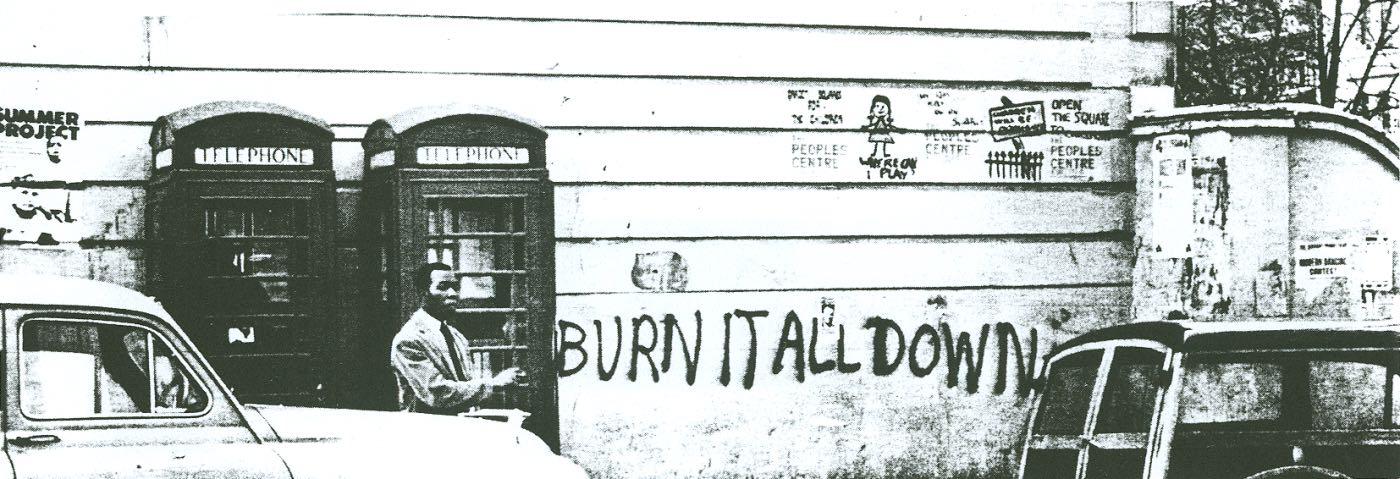

Fig. 1 The corner of Colville Road, Unknown Source (from family records), 1967

Architecture, community and the way we live has always been of special interest to me. This was brought shockingly close to home in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire disaster, visible from my rear window. Gentrification is one of the most obvious manifestations of the class struggle. Kensington and Chelsea, one of the wealthiest boroughs in London is also home to some of its poorest people, with 25% of children living below the poverty line.

For my RCA Master’s dissertation I presented the argument that the bad design of social housing on infrastructural, local and government scales facilitated the gentrification of North Kensington by the erosion of community. From slum landlords and the Notting Hill Carnival, I start by looking how the community has changed over the past 80 years. Taking a tour of the area I study the examples of social housing that were built, including Trellick Tower, once inspiration for J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise, now brutalist icon. Finally I explore new models of shared living, and how social housing can be celebrated in the future.

Fig. 2 Trellick Tower seen from Golbourne Road, Building Sights, BBC, 5 February 1991

INTRODUCTION

It is my opinion that the bad design of social housing at the infrastructural, local and government scales facilitated the gentrification of North Kensington by the slow erosion of community. Through writing this dissertation I hope to expose the substandard treatment the working classes are shown in the borough and highlight the inequality in housing standards. For me it has also been an opportunity to reconnect to my roots in the area.

I myself am a product of the council house system and strongly believe in its role in the welfare state, indeed it is fast becoming the only realistic option available for many low-income families. I was raised by my mother in a one bedroom terraced flat off Ladbroke Grove, I have seen first-hand the reliance on the system but also the power it holds over you. I still class myself as lucky whilst the vast majority in the borough are not. Today, I cohabit a council owned 3-bedroom, 2 storey house in a gated copse in W11 alongside my 99-year-old grandmother and my aunty, her full-time carer. In 2014 the tenancy passed directly from my grandfather to me, and with it the promise of cheap rent and a secure lifelong tenancy with no threat of eviction. It has, however, caused a lot of internal conflict. Due to the privilege of my education, and a family that encouraged learning and curiosity, I will, most likely, find myself in a position in the near future where I can afford private rent, let alone buy. I am not in special need and by me occupying this house I condemn yet another family to wait on the council’s long housing list. This is just my experience of council housing, but many have experienced its complexity.

Why North Kensington? The transient nature of London’s residents, especially those at the RCA who live in West London, never see the complexities within the borough, overwhelmed by the opulence and wealth of the south. The gentrification that has crept in has succeeded in pushing many native to the grove out but can’t hide the stark divide in Kensington and Chelsea, home to both the richest and poorest in London.

We have a long lineage of family in the area, five generations of which have strong links to just one square mile of North Kensington. My great great grandparents were married in the church that once stood on the site of my home. My great grandparents bonded over a musical they heard in the Coronet Theatre on Notting Hill Gate while in service. My grandmother, 1 of 11, was born in 1920 across the road from my mother’s flat and worked as a secretary in Imperial College. My grandfather, a precision toolmaker and community activist, fought against the slum landlords of the 1960’s and the building of the Westway. Life has always been tough. Until the 1970’s the area was regarded as a massive slum, most lived well below the poverty line; my grandparents included, raising five daughters on a meagre London Transport wage. We have seen it, they lived through it and I think it is important to tell their story.

To me community is hugely important, the shared struggles that band strangers together and rise up, in unified voice, for change. Indeed, it is the main power the working classes have. In the words of Percy Bysshe Shelley, my grandmother’s favourite poet, in the aftermath of the Peterloo massacre:

“Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number--

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you --

Ye are many -- they are few!”

In unvanquishable number--

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you --

Ye are many -- they are few!”

Since the crippling of the unions by Thatcher, in my experience today’s youth are largely non-politicised and the masses are apathetic. I believe the poor design of social housing and policy is partly to blame. In this dissertation I will first explore how the community of Notting Hill has changed between the 1960’s and today. How, largely ignored, the poor were preyed upon by slum landlords prompting a number of community action groups to form and fight them. I then look to existing examples of social housing in North Kensington, detailing early successes, architects disconnected from reality and the ineptitude of the local council. Finally, I look to more successful models of social housing and ponder what change the future could bring...